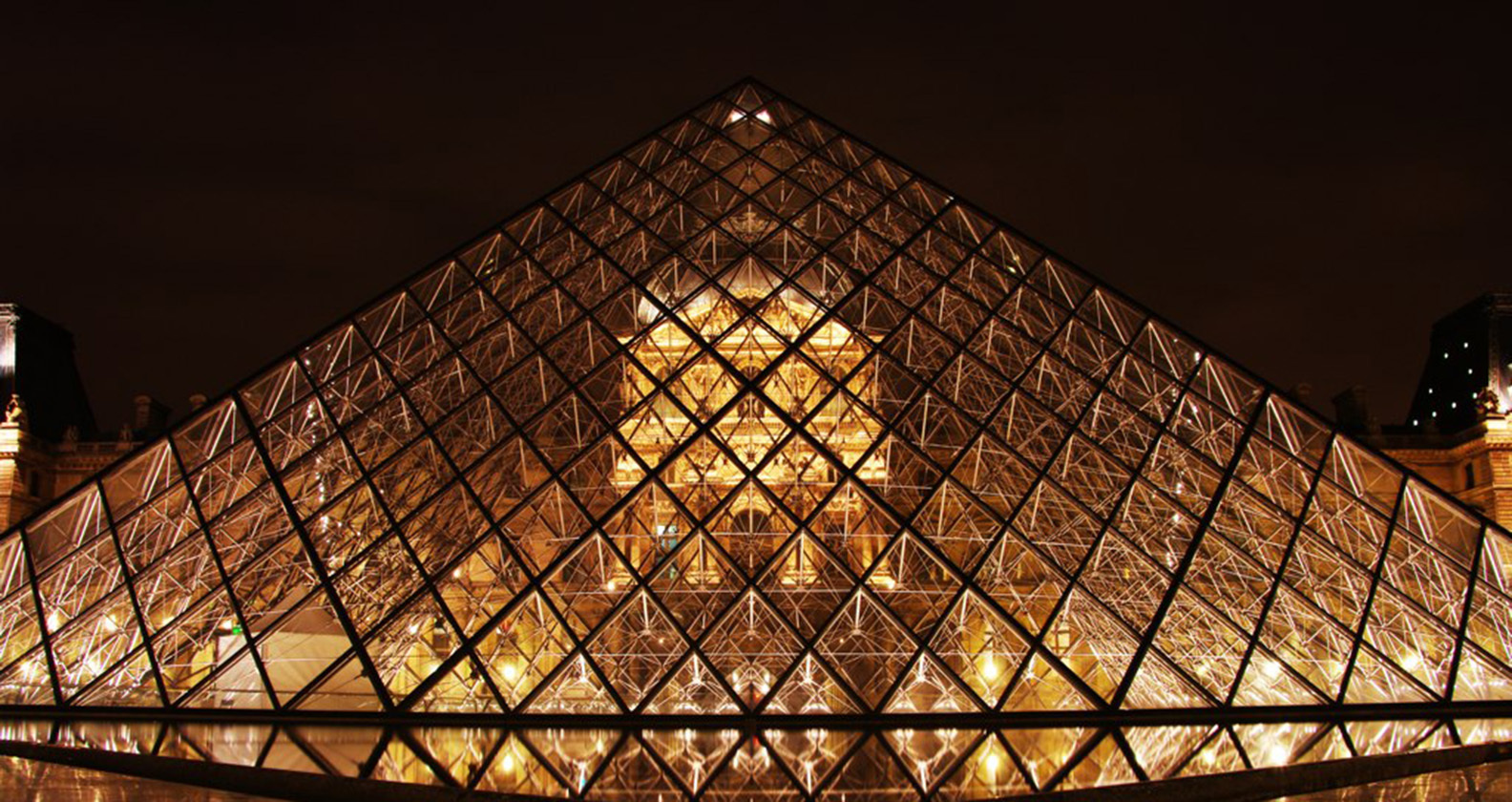

(Above: The glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris. Photo by Club Photo SII)

Leaving an indelible mark on American design history, Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) have influenced the way we consider furniture design, building design, and what it means to blend craft and culture into the way we live. As we celebrate AAPI Heritage Month this May, we look back at some of the designers and architects who paved the way — including women, immigrants, artists, and cultural shepherds who have enduring legacies. These designers are responsible for iconic aesthetics, places, and pieces, many of which are still around today. For those immersed in the study or practice of design, many of these history-making, barrier-breaking individuals may be familiar to you — but their stories and their work are worth revisiting and celebrating year-round.

Helen Liu Fong

(1927 – 2005)

Born in Los Angeles’ Chinatown to Chinese immigrants, Helen Fong is responsible for some of the most iconic — and eye-catching — restaurants in L.A. Breaking barriers not only as a woman, but as a Chinese-American in post World War II America, she received a degree in city planning from the University of California, Berkeley, became employed by the architecture firm Armet & Davis, and was one of the first women to join the American Institute of Architects (AIA). She became instrumental in defining the ultra-modern, space age-inspired Googie aesthetic with her unmistakably bold and futuristic designs that were simultaneously warm and inviting. Marked by dramatically sloped roofs, neon signage, glazing, and utilitarian yet well-designed interiors, Fong’s work — which included diners, coffee shops, and bowling alleys — provided working-class Americans access to good design.

Some of her most well-known designs still dot the city — Pann’s Restaurant on LaTijera Boulevard, the first Norms diner on Figueroa Street, Johnie’s Coffee Shop on Wilshire Boulevard (no longer operational, but still standing), and even Norm’s — all places you might think of when you imagine midcentury L.A. The Holiday Bowl on Crenshaw Boulevard, most of which was demolished in 2003, was another powerful example of Fong’s work, and a symbol of diversity and community. In 2000, a then-employee told the New York Times, “It’s like a United Nations in there. Our employees are Hispanic, white, black, Japanese, Thai, Filipino. I’ve served grits to as many Japanese customers as I do black. We've learned from each other and given to each other. It’s much more than just a bowling alley. It’s a community resource.”

She designed spaces to prioritize social and cultural elements, creating a sense of place, a welcoming experience, and ease of movement through the space for customers and workers. Fong is a big part of the reason these storied L.A. spots were, and are, so beloved.

David Hyun

(1917 – 2012)

David Hyun was born in Japan-occupied Korea in 1917 to a pivotal figure in the Korean independence movement (more below). He immigrated to Hawaii with his family and became the first Korean-American architect in the U.S. in 1950. His work is notable for blending cultural influences of his Korean heritage with architectural modernism. Hyun was a leader in the Korean community, and his philosophy — that architect of the present “best expresses the hope of the future by uniting not only with the past, but by joining cultures both East and West” — was inspired by his father’s work as a political activist and Methodist minister. Hyun’s work is wide-ranging and includes residences, healthcare, restaurants, and auto facilities — all embracing California modernism, indoor and outdoor living, and cultural references.

His most celebrated work is the design and development of the Japanese Village Plaza, a cultural and commercial corridor in downtown Los Angeles, with its signature, 55-foot-tall, red Yagura Fire Tower (a reproduction of a Japanese fire watch tower), imported blue roof tiles, and gabled rooftops. This award-winning project, part of the revitalization of L.A.’s Little Tokyo, turned around the once-declining neighborhood by promoting investment in small businesses and strong urban planning, and is still one of the most-visited destinations in L.A. Not only that, the success of this urban revitalization project, helmed by a Korean American, provided a sense of great pride to Korean and other Asian immigrant communities. Hyun’s own family residence in Silver Lake, constructed in 1993, also ranks among his masterpieces; he spent over a decade planning the home, which blends Eastern and Western aesthetics and beautifully represents the cultural hybridity that Hyun was known for.

Isamu Noguchi

(1904 – 1988)

No list of AAPI — and design icons in general — would be complete without acknowledging the contributions of Isamu Noguchi, a sculptor and designer whose oeuvre included stone-carved busts, monumental public art, playgrounds, furniture, lighting, stage design, landscapes, and architecture. Born in Los Angeles to a writer mother and poet father, Noguchi lived in the U.S. until the age of 2, then Japan until 13. He lived his adult life as a global citizen, traveling and spending time in the U.S. and Japan, but also Mexico City, China, Italy, and beyond developing his monolithic, surreal, and dynamic work, and learning about materials and methods from around the world. His work from this period includes portrait busts, a sculpture representing freedom of the press for the Associated Press Building, and a high-relief mural in Mexico City for the Abelardo Rodriguez Market.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which created fervent Anti-Asian sentiment in America and led to the forced relocation and detention of Japanese Americans at internment camps. Noguchi voluntarily interned at a camp in hopes of promoting community and arts and crafts. He was ultimately detained against his will while he was suspected of and investigated for espionage — a charge which was proven to be false. Then, in 1947, Noguchi developed relationships with Herman Miller and Knoll, designing some of the most lauded furniture designs of the period — including the eponymous Noguchi Coffee Table, his Freeform sofa and ottoman, and the famous Akari light sculptures, all still in production today. In his work, you can see cultural influences from across the globe at play, and notably his Japanese heritage through his veneration of light, meditative environments, and Asian traditions tied to his use of materials. Other notable work includes the gardens for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris; the Lunar Landscape artwork, which is now on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art; and the Zenith Radio Nurse, the original baby monitor.

I.M. Pei

(1917 – 2019)

Ieoh Ming Pei moved to the U.S. from Guangzhou, China, in 1935 to study architecture, earning a bachelor’s degree from MIT and a master’s from Harvard University. Pei is the first Chinese American architect to join the AIA, with a career beginning at Webb & Knapp before he formed his own firm, I.M. Pei & Associates — the associates were colleagues from Webb & Knapp and continued to work for them, though Pei eventually went out on his own. In his early years, he was designing Bauhaus-style high rises notable for the grid-like facades popular at the time. Once working for himself, he produced a vast array of projects, from the Mesa Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado to art museums including the the East Building of Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art, the Des Moines Art Center, and that unforgettable glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris. He became known for a more bold and sculptural geometric style with crisp lines and a heightened intentionality around materiality. Pei believed that modernism could provide the same gravitas and monumentalism as classical architecture, and his award-winning work spanning the globe — museums, concert halls, civic buildings, and academic structures — are a testament. Some of his most notable being the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, and one of his later works, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar. Pei won an array of awards for his work and impact, most notably the Pritzker Prize in 1983.

Kichio Allen Arai

(1901 – 1966)

Known as the first Asian-American architect in Seattle to design buildings under his own name, Kichio Allen Arai was born in Port Blakely, Washington, on Bainbridge Island in 1901. Later, Arai, his parents, and his siblings — he had seven — moved to Seattle. After earning his bachelor’s degree in architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle, he practiced at Schack, Young and Myers before heading off to Massachusetts to get a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard. After graduating and returning to Seattle in the 1930s, Arai entered a difficult professional landscape, thwarted by discrimination and the Great Depression. He did ultimately find work, including the design of the Seattle Buddhist Church, which he was commissioned to work on in 1940. The building was completed the following year, but Arai was unable to relish the finished product — shortly after the building was erected, he and his family were sent to a Japanese-American internment camp, halting his career and life as he knew it. In 1947, Arai returned to Seattle, where he resumed his role as an architect. He is known for designing Buddhist temples in Seattle; Auburn, Washington; and Ontario, Oregon, blending elements of traditional Japanese design with American techniques.