(Above image: Dr. Tara A. Dudley contemplates Dr. and Coretta Scott Kings’ tombs and the Eternal Flame at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change from the third-floor tower room. Photo by Dr. Kathleen Powers Conti.)

This Black History Month, we asked experts on Black design and Black history to tell us about three places that they find personally meaningful — sites that intersect with the Black experience and live on in their individual memories. Places they’ll never forget.

Below you’ll find reflections from Assistant Professor Tara Dudley, Ph.D., who teaches interior design and architectural history at the University of Texas at Austin.

Remembrance and Re-creation | MawMaw’s House

Broussard, Louisiana

My maternal grandmother’s house was essentially a double-pile, single-story house built, more or less, by my great-grandfather, James (DeeDa). The form in which I knew the house was likely an addition to the home on the property purchased by my great-great-uncle Francis in 1930. My grandmother and her brood moved in with DeeDa in the late 1950s or early 1960s. This was the house where my mother grew up. The rear half of the house consisted of the kitchen, little kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom. With no distinguished architectural features or decorative elements, this enfilade of rooms in the rear half of MawMaw’s house connected my childhood dreams and realities. As I tried to write about one space, the others persisted in reminding me of their connectivity and role in shaping a collective and cultural memory.

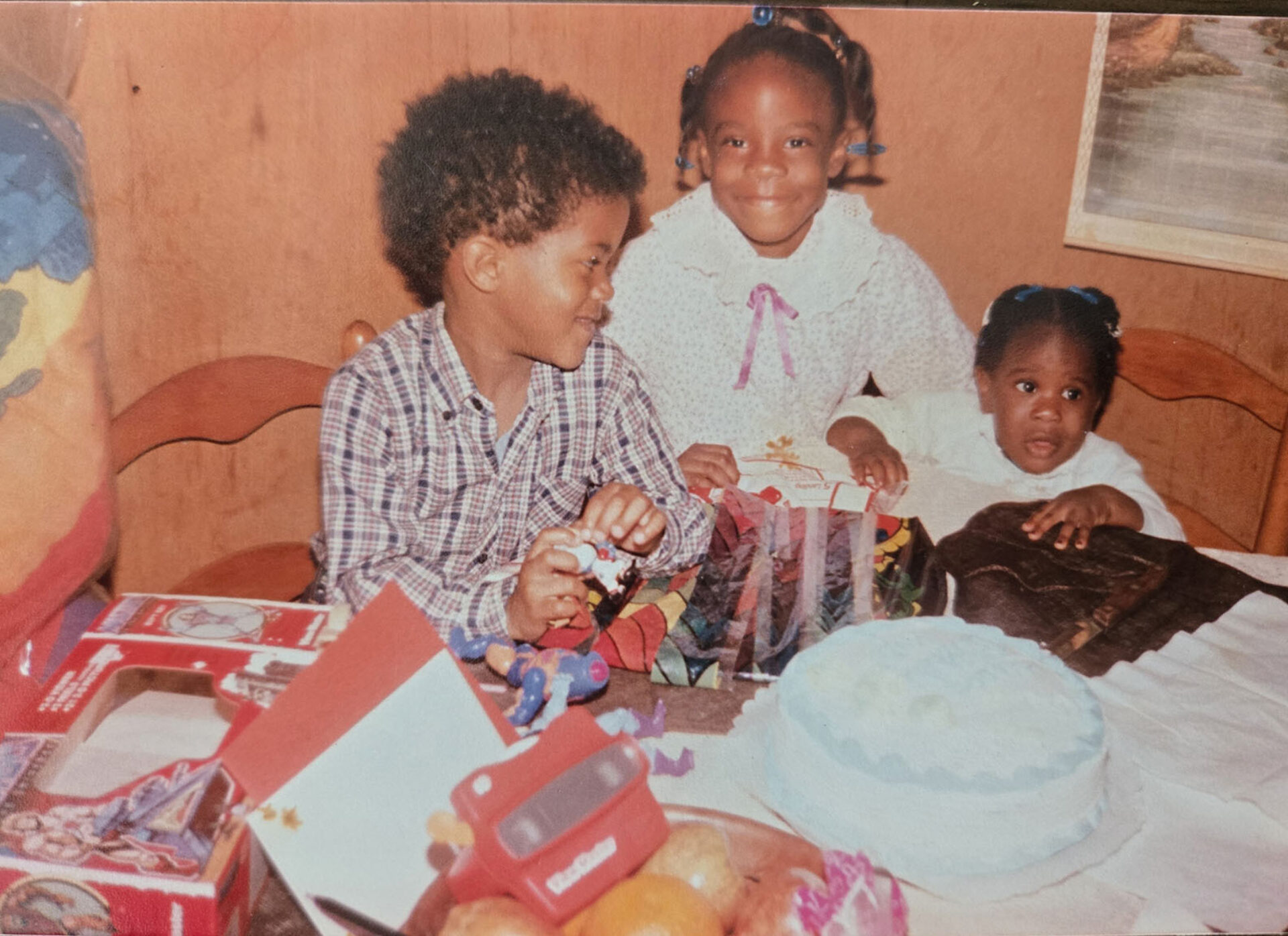

We entered the kitchen from the “girls’ room” — the bedroom in the front part of the house. The stove and sink cabinet were located on the south wall of the kitchen; a window looking out to the backyard was over the sink. The northwest corner was just big enough for a kitchen table. That table was the site of family dinners, after-school snacks (my parents, sister, and I lived next door to MawMaw from kindergarten to the fourth grade), and food preparation for family events. Many birthdays were celebrated at that table with generations of aunts, uncles, and cousins making wishes over candles blown out on homemade birthday cakes.

Because the modest kitchen had little room for storage or large appliances, the “little kitchen” relieved that burden. Right off a doorway in the east kitchen wall, the little kitchen contained the refrigerator, deep freezer, two small china cabinets. If little Tara’s memory serves, a small table along with the top of the deep freezer provided additional work and prep surfaces. The little kitchen was also a site of childhood joy — the perfect room to play “house,” an indoor playground out of the grown-ups’ way on rainy days, and, yes, even the spot for doing homework.

The little kitchen was also a site of childhood joy — the perfect room to play “house,” an indoor playground out of the grown-ups’ way on rainy days.

Tara A. Dudley

Photo courtesy of Dr. Tara A. Dudley.

The “boys’ room” — so-called because it was DeeDa’s bedroom and where my uncles or male cousins slept in later years — was accessed from the west wall of the kitchen. One of my earliest memories (I had to have been around 2 or 3 years old) is pushing open the door from the kitchen with one hand with a doll clutched in the other to be greeted by an older man in a wheelchair. Apparently DeeDa could be a handful; when he gave MawMaw trouble, she would call my mom to bring me over and cheer him up.

After DeeDa passed away and my uncles moved out, the boys’ room became a place of discovery, play, and rest (ugh, naptime). There was the armoire that held family treasures and clothes for playing dress up; the long, low bookshelf that held tomes to introduce us to characters and lands far removed from Broussard, Louisiana; the twin beds that served as tents and trampolines. All these remain etched in my mind, dozens of memories flooding in as I visualize them. Some innate part of my interest in design awakened in that room. The walls were covered with floral wallpaper-like material. I recall white blooms with black centers on a light mauve ground (think the wallpaper that Celie cleans in the kitchen in Steven Spielberg’s “The Color Purple”). The paper was strengthened by newspaper on the reverse with a mesh-like material between the two layers. Although I would have gotten in a lot of trouble for doing so, I used to find the corners where the paper had lifted and peel it off the wall, trying to make sense of the stories and images on the back.

Some innate part of my interest in design awakened in that room.

Tara A. Dudley

MawMaw moved out of the old family homestead in 2006. Vacant, and in a significant state of disrepair, the house was demolished a decade later. Last summer, MawMaw and one of my aunts returned to the family land. In form, the double-wide manufactured home that now occupies the site is not unlike MawMaw’s old house. While the simple, lauan wood-paneled walls of the kitchen and little kitchen are gone and flowers no longer bloom on the walls of the boys’ room, I move through the new spaces and remember partitions that didn’t separate but created a world. The new kitchen window looks out on the backyard in almost the same spot as the original — past and present colliding, re-creating, remembering.

Reflection and Reverence | Ebenezer Baptist Church

Atlanta, Georgia

Historic furnishings reports are my favorite cultural resource management and preservation planning documents to research and write. Over the course of my career, I have contributed to or written over a dozen historic furnishings reports, including 11 for sites under the stewardship of the National Park Service. During the late 2010s, I had the opportunity to develop reports for three sites at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta — the King’s birth home, the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Fire Station No. 6. Each property brought forth research and interpretive challenges as well as moments of awe and contemplation.

One unexpected space — the third-floor room in the northeast tower of Ebenezer Baptist Church —impacted me the most. This room is unknown to the public and the tourists visiting this venerated site of Black history, the church where Dr. King and his father preached and where the King family led the fight for racial equality through their ministry and civic engagement. The “first unit” (present-day basement or ground floor) was completed in 1914. Originally unoccupied after the “second unit” (upper levels) of Ebenezer Baptist Church was completed in 1922, the third-floor tower room was used at various times according to the needs of the church. When the church underwent renovations from 1955–1956, the third-floor tower room became the church’s temporary office.

This office was entered via a steep stair from the balcony level. Once the renovations were complete, the church office relocated to the education building east of the church proper. The stair to the temporary office probably was removed during a 1970–1971 renovation, and the opening likely was covered by the suspended ceiling. Today, access to the third-story tower room via a pull-down attic stair in the ceiling of the northeast tower is hidden from public view.

Photo by Mobilus In Mobili, CC BY-SA 2.0

Photo by Dr. Tara A. Dudley

My colleague and I were lucky to be granted access to the room, which has been unused for decades. The room has tongue-and-groove pine floors. In the mid-1950s, the floor was covered with 9-inch-square red asphalt tiles; some are still present today. The masonry walls were originally left unfinished. During the 1955–1956 renovations, the walls were plastered and painted green, like other parts of the church building’s towers. To accommodate a temporary office, a wood-frame ceiling and a wood-frame wall were installed and plastered. The ceiling was removed sometime before 2001. No archival or photographic documentation of the appearance of the 1955–1956 temporary church office in the third-floor tower room have been located.

Not by design, the room’s east-facing windows happen to provide an unencumbered view of Dr. King’s and Coretta Scott King’s tombs and the Eternal Flame over the reflecting pool at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. There, in that empty, unadorned, and unfurnished room, bathed by the abundance of natural light that the windows let in, I felt the magnitude of Dr. King’s legacy more than in any other space in the park. I took a moment to just be, to think about the people who came before me so that I have the privilege to do work that honors Black history. I was blessed to partner on that project and visit the space with a colleague who captured that moment in time.

Reckoning and Restoration | The Slave Quarters Building

Neill-Cochran House Museum, Austin, Texas

The Neill-Cochran House and Slave Quarters building, owned and operated by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in Texas since 1958, were constructed under the supervision of master builder Abner Cook in 1855. While the site’s prominent property owners and high-style Greek Revival architecture have been studied, the lives of Black Austinites and European immigrants who were associated with the site were not part of that narrative. In 2016, Dr. Rowena Dasch, the museum’s executive director, came to the realization that the structure behind the main house, called the “dependency” since the site opened to the public in the 1960, would have been a building inhabited by enslaved people. Various professionals, using best practices at the time, conducted restoration work on the building in the 1970s and early 2000s. In 2019, I began collaboration with Dr. Dasch on what has now been a multi-phase effort to restore and interpret the Slave Quarters building.

A limestone structure with 14-inch-thick loadbearing walls, the Slave Quarters building is two stories, featuring one room on each floor. The second story is accessed by an exterior stairway. Originally, access between the floors was also gained through an interior ladder. A small square opening, just big enough for a person to climb through, was cut through the floorboards on the east side of the building. To access the second story from the ground floor, and to save the already limited square footage, a simple ladder would have been placed near or built-in against the east interior wall so that one could move between floors. The first floor originally had a packed dirt floor, about a foot lower than the present threshold. The most prominent feature in the first-floor room is the brick set kettle built into the northwest corner. The second story of the building has cedar floorboards.

Photo by Ted Eubanks

Photos by Dr. Tara A. Dudley

During restoration of the building from 2022-2024, the historic vertical circulation was restored by locating and opening the pass-through and installing a reproduction ladder of cedar posts. We also excavated through a 12-inch-thick concrete slab topped with brick pavers to reveal the original floor depth. On the first floor, craftsmen removed a false ceiling and restored the exposed ceiling, which also functioned as the second-story floor. Likewise, a false ceiling in the second-floor room was removed to expose the underside of the roof, which forms the room’s ceiling. This was, perhaps, the most magical and rewarding part of the restoration project. Although it is a simple, early gable roof system using heavy rafters with internal bracing, the roof of the Slave Quarters building is a masterpiece crafted by enslaved carpenters.

Four diagonal hip rafters are supported by cross bracing. Additional rafters serve as the foundation for the exposed boards that form the roof deck. The rafters are joined to the wall plates on the east and west side of the room with mortise and tenon joinery. This work of art allows one to experience firsthand the skill of the men who crafted it. As the only intact, recognizable, and publicly accessible slave dwelling in Austin, the Slave Quarters building is a significant site to learn about urban enslavement in Texas.

The roof of the Slave Quarters building is a masterpiece crafted by enslaved carpenters.

Tara A. Dudley

Upon completion of the restoration project, our team decided not to attempt to recreate historic furnished interiors. Instead, the rooms are unfurnished so as not to disturb the fabric of the space and to allow visitors to have their own experiences. I was able to identify several previously unknown individuals associated with the site. Visitors can learn about these enslaved men, women, and children — as well as the Black and European immigrant domestic staff who would have encountered the building — through small text panels on easels, an audio tour, and a newly developed augmented reality tour.