The pathway to design is different for every individual, but a constant is education. Whether a person takes a direct, traditional path into the design industry, or finds their way into the profession an unexpected route, continuous learning about the built environment—and how to shape it to serve individuals and communities—is essential. For young people, one way to step foot in the field of design is through IIDA’s Design Your World (DYW) summer program, an education pathway program created to build equity and diversity in the industry by exposing high school students to the possibilities of a design career in design.

This past summer, a skilled group of DYW instructors taught students in Miami, St. Louis, and Chicago. We were curious—what did instructors’ own design education look like? We asked Lindsey Buening, IIDA, an instructor at Maryville University of Saint Louis; Chelsea Jackson-Greene, an interior designer at Perkins&Will Chicago; and Davey Friday, an urban designer at Perkins&Will Chicago to share their design school experiences, what they wished they had learned as students, and how to better prepare students for the future of the industry.

Responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

DYW St. Louis Instructor

Maryville University of Saint Louis

DYW Chicago Instructor

Perkins&Will

DYW Chicago Instructor

Perkins&Will

Tell me a little bit about your design career journey. What drew you to design?

Lindsey Buening: I had a nontraditional path to design. When I graduated high school, I aspired to be a journalist, which to me meant telling peoples’ stories and advocating for meaningful change. I didn’t stay in school long and instead traveled around, working in the service industry, engaging with people from all walks of life and listening to their stories. I stayed with my folks and helped them renovate their historic home and for the first time realized interior design could be a career path. I felt like it would be a good fit for both my logical and creative brain. I went back to school and graduated from Maryville University with a B.F.A. in Interior Design. I worked as a commercial designer in St. Louis for about 12 years before I decided I wanted to stretch what being a designer meant to me. Through a series of fortunate events, I landed in a faculty position back at Maryville, where I feel like I get to help shape the future of design through education.

Chelsea Jackson-Greene: I come from a family that always encouraged me to explore the arts as a career. As a child I expressed interest in architecture but wasn’t sure if it was the path for me. My first two years of undergrad, I was studying art history and general fine arts in hopes of landing a job working in museums or art sales. When I studied the history of installation art and how interior spaces can influence human emotions, mine included, I decided to officially pivot to study interior design. I soon transferred to Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) in 2013, got my B.F.A. in Interior Design with minors in Design for Sustainability and Architectural History. After graduation, I stayed in Savannah to work at a small architecture and urban design firm until the pandemic, then began working at a midsize firm. In February 2022, I began working at Perkins&Will and later relocated to Chicago.

Davey Friday: I started my design career with a pirated version of the Adobe Creative Suite at about 14. I had dreams of starting a clothing line, and I used my stolen software to familiarize myself with the design process. I have been able to draw since I was a young child, and as my entrepreneurial gene started to kick in as a young teenager, becoming a designer seemed like the logical next step in my evolution as a creative.

What areas do you specialize in? Does your current role match where you thought you’d land?

LB: My resume experience is mostly in corporate interiors, but I would say that I specialize in design thinking and the process of design. I’ve always loved how research leads to a concept and evolves into a design that eventually comes to life. I’m fascinated with how the design process helps us to imagine a different future and creates a way towards change, step by step. I had professors that encouraged me to consider teaching when I was still in school, so it’s always been in my mind as an option.

CJG: Initially, I wanted to work in hospitality, retail, and exhibition design because those were the projects I looked at the most for design inspiration. It wasn’t until my capstone project during my senior year of college, where I designed a community center in a historic building, that I was able to really explore the ability for buildings to heal and support users through design interventions. That informed the direction I wanted to take in my professional career. At Perkins&Will (PW), I am currently in corporate interiors. I’ve also recently had the chance to work on science/tech and social purpose projects.

DF: Currently I’m an urban designer, with master’s degrees in architecture and landscape architecture. I always knew I wanted to get paid to design, I just thought it’d be as a fashion designer as a kid. As my interest and understanding of cities and the way we live in them expanded over time, the evolution from designing the clothes people wear to the places they live, and work was inevitable. As my understanding of design expanded, so did my understanding of the type of influence I could have by harnessing design.

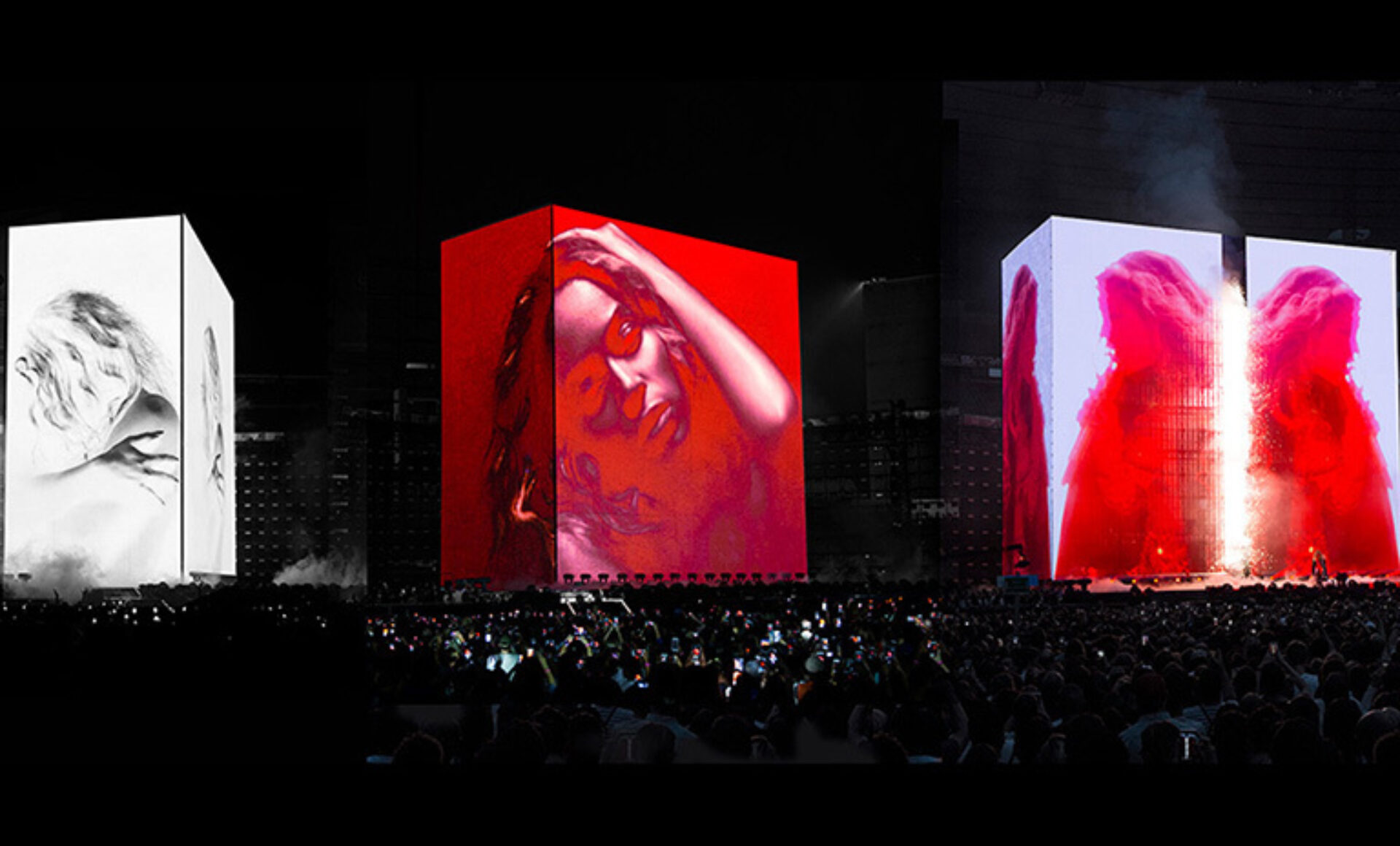

Image courtesy of Chelsea Jackson-Greene

Image courtesy of Davey Friday

In design school, what did you feel was missing from the curriculum? What would you have changed?

LB: When I give advice to students, it’s usually that they should take as many courses that expand their worldview as possible, anything that can help to give them a perspective on the world other than their own helps to make them a better, more creative, and compassionate designer. I also recommend taking as many psychology courses as possible. Understanding the “why” behind human behavior supports creating spaces that work as intended and helps us, as designers, navigate the personalities involved in making decisions about how those spaces take shape.

CJG: I deeply appreciated that the curriculum at SCAD wasn’t overly technical or overly conceptual and really offered a mix of both formats, with opportunities to explore other interests through minors. I have expressed concerns that current college curriculums are not consistently teaching Revit or the Adobe Creative Suite in a way that leaves graduates career-ready. I learned the basics of both Revit and Adobe in college but took additional classes outside of the mandatory curriculum to be better prepared for graduation. That was over seven years ago, and I don’t believe the curriculum has evolved beyond a basic understanding of these softwares. I’ve now worked at three firms, ranging in size, scope, and sectors, and all have required the use of Revit and Adobe daily.

DF: I think the intersection of economics and policy was missing from design school. There are many roadblocks in terms of policy and financing that all designers will ultimately run into, and they feel like running into a brick wall full speed when we encounter them. It is imperative that designers understand the realities we face in the world, so we can be better prepared to face the challenges as they arrive.

If you could make your own design school curriculum for aspiring design students, what would it consist of?

LB: I feel like I had the opportunity to do this with Design Your World. I’m proud that our team was able to craft a curriculum that introduces students to interior design as an industry and presents foundational design skills through a lens of empathy, equity, and inclusion. Our first week, we focused heavily on specific skills and principles: color theory, elements and principles of design, design process, sustainability, universal design, scale, drawing types, diagrams, and concept development. In the second week, students practiced putting all of this together into their own designs for an imagined community space.

madisonbowermaster.com

CJG: My ideal curriculum would include these courses:

Curiosity 101: This course would teach designers how to get curious, utilize unique research methods, and find design inspiration outside of algorithm-based platforms.

Lost Art of the Napkin Sketch: A fun hand-drafting class using random mediums. Quickly being able to hand draft a detail, plan, or perspective holds immense value when you need to get an idea out fast.

Sustainability and Designing for Resilience: Students would learn how to research, plan, and implement sustainable methods to help combat climate change.

Columbia College Chicago

Architectural History: So much of the conceptual thinking about contemporary design today is rooted in prioritizing “modern/Western” architectural theory and language. Very rarely does this approach consider the innovation and inspiration that can be found in African, Asian, and Indigenous design.

Speech and Presentation: Our role often involves being able to communicate our ideas to clients and users who may not be familiar with design terminology and concepts. Being able to leverage a combination of verbal, written, and graphic presentation skills has tangible benefits to career growth.

Construction Documents: This course would teach construction document best practices and tips with relevance to a design project students would work on.

User Survey and Engagement: Learn how to study and strategize data collection, formulate questions, and synthesize user responses for creating better design solutions. Would probably include learning the basics of Excel, too.

DF: My personal design curriculum would have a heavy emphasis on psychology and sociology, particularly through a historic lens. Designers need to know why people behave the way they do, why they make the choices they make, and how that has changed over the course of time. Armed with that information, I believe designers can maximize their influence.

IIDA

As a Design Your World (DYW) instructor, how did you approach teaching the curriculum? Which design concepts did students find most engaging?

LB: The approach for the DYW curriculum was to help students understand and build on the design that they see in the world around them, and to recognize all the decisions that go into the creation of spaces. The students were most engaged when we did something that expanded their perspective. For example, one activity was to describe colors using only verbs, sounds, or emotions. Another favorite was an empathy exercise. Their understanding of how design can affect peoples’ lives really began to shift during this activity. It was a delight to observe. designs.

CJG: Our students were predominantly from the South and West sides of Chicago, areas known to be systematically disenfranchised within the built environment. It was important for us to give the students the opportunity to cultivate imagination of what spaces should look and feel like. We spent time developing design concepts through word mapping and collaging, took several field trips, and taught students how to find design inspiration. Students seemed to really love how an initial concept could turn into a formal design articulated through space planning, furniture, and finishes.

DF: I approached teaching the curriculum the way my favorite design professor, Leslie Johnson, did. Leslie taught with empathy, clarity, and repetition. I was intentional about meeting the students where they were skillswise, and did my best to communicate the way they could sharpen their skills clearly and repeatedly. I emphasized the importance of practice and repetition in developing design and drawing skills.

You taught students a lot during DYW. What did students teach you?

LB: As a professional, we purposely build efficiency into our work lives and the problem-solving we do every day. But that can stagnate creative thinking and close us off to innovation. As an instructor for DYW, I was mindful to help support and explore students’ ideas, even when they didn’t align with some of my engrained efficiencies. The students helped to remind me of the importance of open-mindedness when seeking solutions to complex problems. It was so much fun to explore some really wild ideas with them and to collaborate on how to get to real-world solutions.

CJG: We had a student who showed up with several books from the library on Japanese interior design and the Danish hygge concept. He was so excited to find relevance in pre-existing design philosophies and apply it to the program. I immediately went to the library after class that day and grabbed two books on topics I found interesting. It made me not only appreciate the importance of stepping away from the computer and picking up a good design book, but also how there are so many global design philosophies we can utilize to solve design problems.

DF: I think the students reaffirmed my belief that people are capable of anything when they are encouraged and when they give their best effort. They taught me how to push someone to be better and challenge them without being negative, mean, or discouraging. They showed me how to communicate design with teens in a way they can be receptive and grow.

IIDA

IIDA

What do you think is the most important thing for students to learn before coming into this industry?

LB: I believe design is imagining the future we want to see in the world. If students enter the industry with a curiosity and compassion for the people that they are designing built environments for, combined with an understanding of design thinking, then they’ll be well prepared for a career as a designer.

CJG: Be adaptable and remain curious. Our industry and role include constant change. Clients may have budget constraints, contractors may have to push back on a material or technical application, you may be juggling projects in different phases, and graduates will need to be prepared to pivot and create anew when these things come up. Typically, it will be some time before a fresh graduate is leading the design for a project. This doesn’t mean young designers should stop pursuing and investigating their own aesthetic preferences, even if it means you won’t be able to implement them right away. Stay connected to the things that got you interested in design, and try new things that can be sources of inspiration.

DF: I think the most important thing for students to learn is the necessity of failure. Failure after trying your hardest is a necessary experience to embrace. The fear of failure prevents many people from attempting to do great things. Growth is on the other side of failure. The lessons learned from the experience of failure are invaluable and can greatly inform what success can look like with recalibration. That is why repetition is key. Repeatedly attempting something, even after failing, gives birth to greater understanding and refined skills, which are the foundation of success at any endeavor.

What do you hope the future of design, and the future of design education, looks like?

LB: Design impacts everyone, every day. It’s optimistic and forward-thinking, imagining the world at its best. I would love to see the industry lean into our power to transform our world in a way that centers equity, inclusion, sustainability, and social justice. Design education should prepare students to enter the workforce ready to tackle complex problems with innovative solutions that center the diverse lived experiences of people. We are in the business of creating change, so I would hope that we are working towards the change we want to see.

CJG: I think the threat of climate change will require systems to change and create serious solutions. I believe design education can be at the forefront of how we pivot the way the world operates. I hope the future of design involves prioritizing sustainable design beyond accreditation, building culturally competent spaces for community rather than mass consumption, and reimagining the language and aesthetics we use to qualify which spaces are resilient, beautiful, and elegant.

DF: I hope the future of design is more widespread. You don’t have to be a designer to benefit from an understanding of design, even at a surface level. I hope that design education is wider-reaching, more inclusive, and more equitable—more affordable, more appreciated, and more thought-provoking. For far too long, design has been reserved for the privileged, yet it affects every single human on this planet.

Visit the table of contents for more Perspective: State of Education.