This is an excerpt from the IIDA Industry Roundtable 27 Report.

When was the last time you experienced awe? Maybe you witnessed sunrise in a lush setting, gazed up at a glittering expanse of stars in a clear night sky, or saw a tiny human take its first step.

Whatever the stimulus, there’s nothing quite like that feeling of awe — the immensity of it, the wonder, the way it takes you by surprise and makes you feel small in the vast scale of the universe. Awe is life-affirming, revelatory, and rare, and it’s become something of an obsession for Upali Nanda, Ph.D., global sector director of innovation at HKS.

“Awe creates little earthquakes in the mind,” Nanda says, quoting a scientific paper. “It literally changes our framing with which we see the world.”

What else does the science show? That awe can promote happiness, health, and social interactions, playing a role in how humans get along and work together. In essence, awe is an incredibly potent emotion — and a powerful design opportunity.

Global Sector Director of Innovation

HKS

At the IIDA Industry Roundtable 27, Nanda, who is also a partner and executive vice president at HKS, shared the simple elements that create awe, how it affects our brains, the challenges that come along with creating awe in the built environment, and why designers should start prioritizing emotion and valuing the immeasurable.

The Anatomy of Awe

Good design, Nanda argues, inspires intended emotions, such as joy, happiness, and comfort, and awe has the power to unlock those feelings. When we experience awe, the part of our brain that’s constantly in play — the default mode network, which keeps us focused on ourselves and our immediate needs — is slightly deactivated. Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex, where our higher-level thinking happens, and the anterior cingulate cortex, which regulates emotions, rev up.

Awe enables us to “think further and reach further,” Nanda says, to step outside of ourselves and realize, “I’m just small. In the vastness of the universe, I’m tiny.” That perspective prompts a greater sense of connection to others and feelings of gratitude. “I keep thinking about awe being this door we open through which happiness walks,” Nanda says. “It’s the portal.” Like many good things, awe doesn’t come easy. To experience awe, and to create it, there are two criteria: The stimulus must be perceptually vast. (“It’s something that’s bigger than you, that feels bigger than you,” says Nanda.) And it has to be surprising.

The formula is simple: vastness plus surprise equals awe. But sparking the emotion is remarkably difficult, because it’s tough to replicate. Once you’ve experienced awe, you can’t experience it the same way again. “It has a time-bound component to it, which is where the magic comes from,” Nanda says. That’s a tough needle to thread for designers, who create spaces that must produce positive emotions repeatedly, for hundreds or thousands of people over many years.

Obstacles to Creating the Magic

There are distinct challenges to designing for awe, Nanda posits. A major impediment is the design industry’s overemphasis on representation through artifacts, such as sketches and renderings. “We confuse the artifacts we create with the experiences we intend,” she says.

Imagine, Nanda says, that a client said, “we are going to sit here in what you designed, and I want to feel what you told me I’d feel … and I want people who come in to feel it, and I want you to tell me how you’re going to keep that feeling fresh.” Designers often aren’t accountable to and rewarded for the experiences of end users, she adds — they’re rewarded for representations.

Another obstacle to generating awe? We don’t measure for it. “Why do we measure function but take emotion for granted?” Nanda asks. Two decades of her career have been spent grappling with how to link design intent to incredible outcomes; she’s found that a fixation on what can be measured ignores the less perceptible but very real parts of what make us human. “Why do we link design intent to things like purely function? That’s not an incredible outcome. Somewhere along the line,” she says, “we stopped valuing the immeasurable.”

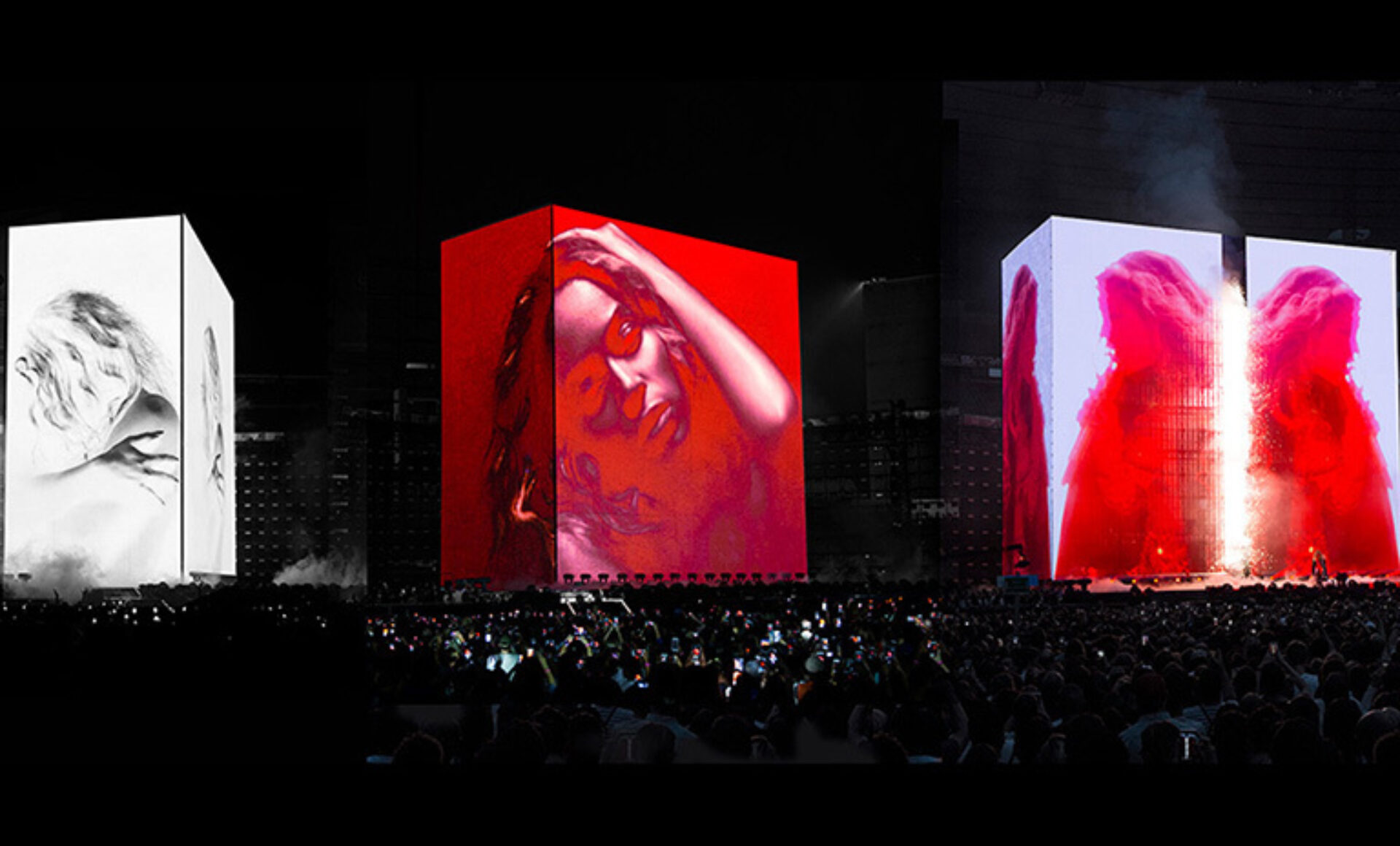

The small devices glued to our hands also obstruct awe. Looking down at our phone screens prevents us from noticing moments of wonder in our daily lives. Our world has become two-dimensional, Nanda says, and this fragmentation — constantly switching between our physical and digital lives — is a complexity of our times that design must navigate.

“What does it even mean to be somewhere? What is presence, what is place, when you are always going to have a digital layer with it?” Figuring out how to interweave the threads of physical and digital presence to elicit emotions like awe is one “wickedly beautiful” design challenge that lay ahead.

Photo credit: Chris Dilts

Photo credit: Chris Dilts

How to Push Design Further and Find Awe

Tackling a knotty design challenge, or any pressing issue, is made easier with a range of thoughtful perspectives — but often, silos get in the way. Designers don’t talk to scientists, and vice versa, Nanda says. “We don’t think creatively together because we are either disciplinarily arrogant and don’t reach out enough, or we’re timid and don’t reach out enough. But this has to change.”

She has four proposals to bridge divides and pursue ever more human, awe-inspiring design:

- Make practice a creative lab. What if every design project was a lab focused on the art and science of being human — with the ultimate goal of unlocking new ways of thinking? One way to experiment is through sensthetic salons, where design is experienced in ways that engage multiple senses, rather than simply through visual artifacts.

- Have play dates. Assemble artists, designers, and scientists to have shared experiences, then brainstorm, riff, and figure out ways to practice creating designs that enrich users’ lived experiences.

- Create “lived experience awards.” These would celebrate how people feel in a space and not just what presents well. This would require paying more attention to and measuring for experience in the built environment. “The tragedy of our profession,” Nanda notes, is that designers give the concept and the drawings, “but when someone experiences the magic, we’re not there. And maybe that’s something we should change.”

- Commit to measuring the immeasurable. The biggest disservice of evidence-based design is that it has become prescriptive, Nanda says. The intent was to probe what makes a good outcome then push the boundaries of design further, never to evaluate only that which can be easily measured. Channel Einstein, who urged “imagination first, investigation later,” Nanda says, “not the other way around.”

The How-To: 4 Steps to Create Awe

Awe equals vastness plus surprise. Easy in theory, tougher in practice. Luckily, Upali Nanda identified a method to create awe, in four clear steps:

- Build anticipation.

- Design the approach.

- Frame it.

- Have a sensory onslaught.

Here’s an example that illustrates the above techniques. In “The Temple in the House,” by architect Anthony Lawlor, the author describes a Japanese teahouse on a hill overlooking the sea. Guests invited to the tea house are told of the beautiful setting — there’s the anticipation. Upon arrival, they approach a garden gate where a grove of trees had been planted, blocking the view — that’s the well-designed approach. According to custom, guests are prompted to wash their hands and mouth before entering the teahouse. When they bend down to access the water, they spot an opening in the trees that offers a view of the sea — there’s that framing. And as they take in that spectacular view from an unexpected position, they experience a sensory onslaught. There’s the awe.

Read more Perspective: Designing for Joy here, or the full Industry Roundtable 27 Report here