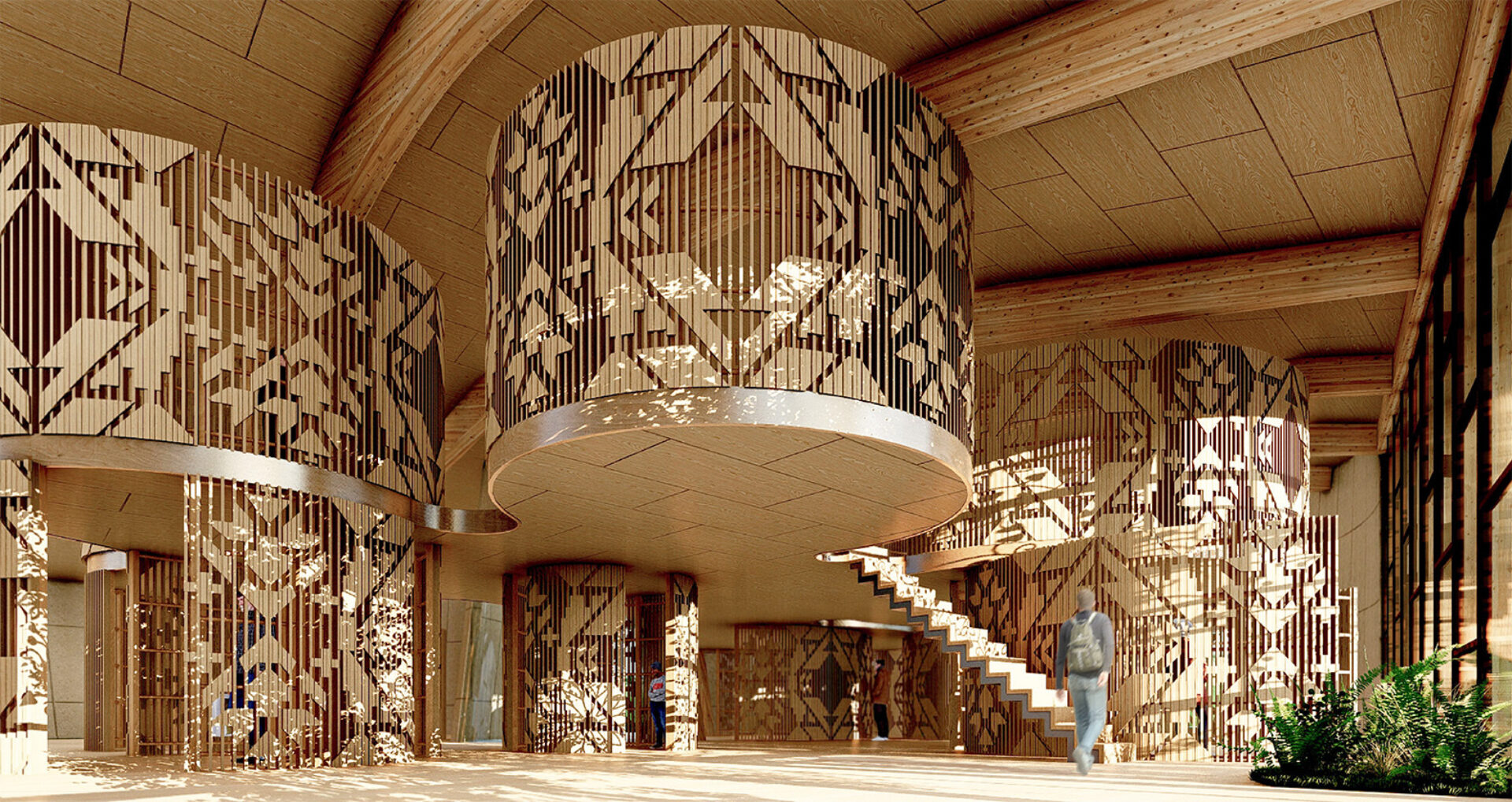

(Above: Chippewa of the Thames First Nation Heritage Hub, a cultural center and governance building improving community access to cultural lifeways and economic development. Rendering by Tawaw Architecture Collective)

Fascinated by the cultural storytelling that she saw in the built form during her seven years backpacking around the world, Wanda Dalla Costa, AIA, (Saddle Lake Cree Nation) returned to North America with a vision for the future. She wanted to bring that expression of Indigenous cultures and deep reverence for ancestral wisdom home to her homeland. Why couldn’t we in Canada utilize the lessons learned from centuries of living in this land into the forefront of not only our design, but the design process itself? Not only recognizing how Indigenous cultures took a more localized approach to designing for the immediate ecology, but also in how we approach design as a collaborative community action.

Principal at Tawaw Architecture Collective, and Director of the Indigenous Design Collaborative & Institute Professor at Arizona State University’s (ASU) The Design School, Dalla Costa has reimagined what it means to be an architect and designer. She approaches her process and designed places from furniture to the urban environment through a lens of resiliency, and transition design—design with the goal of shifting society towards a more sustainable future by considering the interconnectedness of social, economic, political, and natural systems to address problems at all levels of scale in ways that improve quality of life. We connected with Dalla Costa for a conversation about optimism, the concepts of co-designing and Placekeeping, and Indigenous technologies as sustainable strategies.

A Value System of Relationality

We have really beautiful value systems in the Indigenous worldview, and one of the beliefs is belief in ethical relationality—which is the stewardship of all living things. This includes not only the people, animals and plants, but also aspects that some people would consider inanimate, such as mountains, rocks, and water bodies. What's special about this value system related to the natural world is that humans are not elevated above the other parts. In this system, we all have to survive because the system is dependent on itself and is only as strong as the strongest elements in that system. It’s a humbled value system that I think brings a really different perspective into the world of sustainable design.

Design is turning collaborative. It's turning plural, participatory, and distributed. It's starting to integrate the interconnectedness of all life. I have never seen so much interest in Indigenous design and philosophies. I continuously have to ask myself, why? In Designs for the Pluriverse, Arturo Escobar talks about this notion of a transition imaginary, the rethinking of dominant models in any field, including sustainable design and designed interiors, looking for new, more sustainable, and resilient models.

“I realized that there was something really special about my own homeland, my own culture, and I needed to uncover it and understand it.”

Wanda Dalla Costa

We as designers are starting to see that the cities and spaces, the interiors, and buildings that we have been creating have been driven by a very small “expert-driven” group of the “great forefathers” of architecture. As people are starting to doubt these dominant models, we're seeing a large push for diversity, equity, and inclusion and reconciliation of indigenous people at the same time. Design practice is moving towards a collective-driven value system from which new modalities emerge, this movement is assisted by the issues happening in our world right now—ecological devastation, climate change, and inequities that are becoming more and more visible. We’re facilitating a process that is very localized, socially driven, situated, and open-ended. And this transformation is happening in many fields, including design, and is starting to create an opening.

There are one of over 1,200 different, indigenous, diverse, indigenous cultures that have these beautiful, old, ancestral belief systems that have ingrained values embedded within that I think could lead us to a brand new place. I don’t think we have to push much to get people to understand and see what we believe. We are finding that there is a huge movement out there, and we are just one activist group that is taking part in this transition imaginary. It's really great.

Integrating Lived Experience

Every project we work on integrates the lived experience, we co-design and co-lead everything with all of the knowledge brokers—elders, community members, master builders, and all of the team of people that we engage with in the work that we do. The sum of all of that lived experience flips design on its head because we see that those dominant models of practice can be upended, be broadened, and can be enlarged to include things like value systems, but also Indigenous triad design, which we work with in our firm.

The concept of Indigenous triad design comes from Amos Rapaport. He uses more formal terms; behavioral, social, and ideological which we have converted into the more user-friendly terms of worldviews, identity, and lifeways. Worldviews—which principles of ecological stewardship are worldviews, and how can we bring them into our projects? Lifeways are simply how we use spaces, the behavioral ways, for instance, a powwow, round dance, or ceremonies or sweats. These are all lifeways that are vitally important for Indigenous peoples, the resilience of cultural continuity. And then, finally, it's the identity piece. You know, “What can we do in this building, this place, this interior?” It’s this master plan that speaks to the identity of the local people. What we're really aiming to do is radically reimagine through the lens of the lived experience of our communities and staff. As one elder said to us, “You know whose lodge you're in when you get there.” And so those are what we're pushing on in the field—designing for cultural continuity and conserving the traditional culture.

I think one of the most exciting projects we're working on now is in Alberta, Canada. We're working on a master plan with a first nation, and their goal is to indigenize the entire master plan. We've worked all the way from the furniture scale to buildings to also an urban scale— I love working at an urban scale! There is commercial development designed for non-Indigenous people to come and visit, but the community wants to make it special. We’re integrating the old ways like old sporting events and cultural activities that keep the community vibrant and resilient into the plan. The project is led 100 percent by Indigenous people and the experience of self-definition will produce something unlike anything we’ve seen before in an urban plan. This is what we aim to do with our work—productive disruption. Using the lived experience to radically reimagine all scales of design.

Reimagining Education

I realized that I could only have so much impact by doing this work through an architecture firm. And so my mission when I entered Arizona State University was to bring the Indigenous placekeeping framework, our trademarked process that we've been using over the last 30 years, to the school to see if we could mobilize a radical reimagining in an academic setting. And honestly, I believe this generation of university students is absolutely open to the field of Indigenous design and really all sorts of socially driven movements within the field of design.

We've so long relied on that limited circle of voices, the “great forefathers” of architecture, and a design process about building empathy. But what does that really mean unless you have a full understanding of what it means to be Black or Latinx or Indigenous? You need those voices at the table and this generation is ready for change. They see that our world is changing, and we have to respond to that.

I think that we have a very open generation of students right now. And the movement that we're undertaking seems to be received well with them. For me. It's about introducing a new, broader narrative, and my ultimate dream is that if we change the process in architecture, I actually think it will change the outcomes. I'm very hopeful.

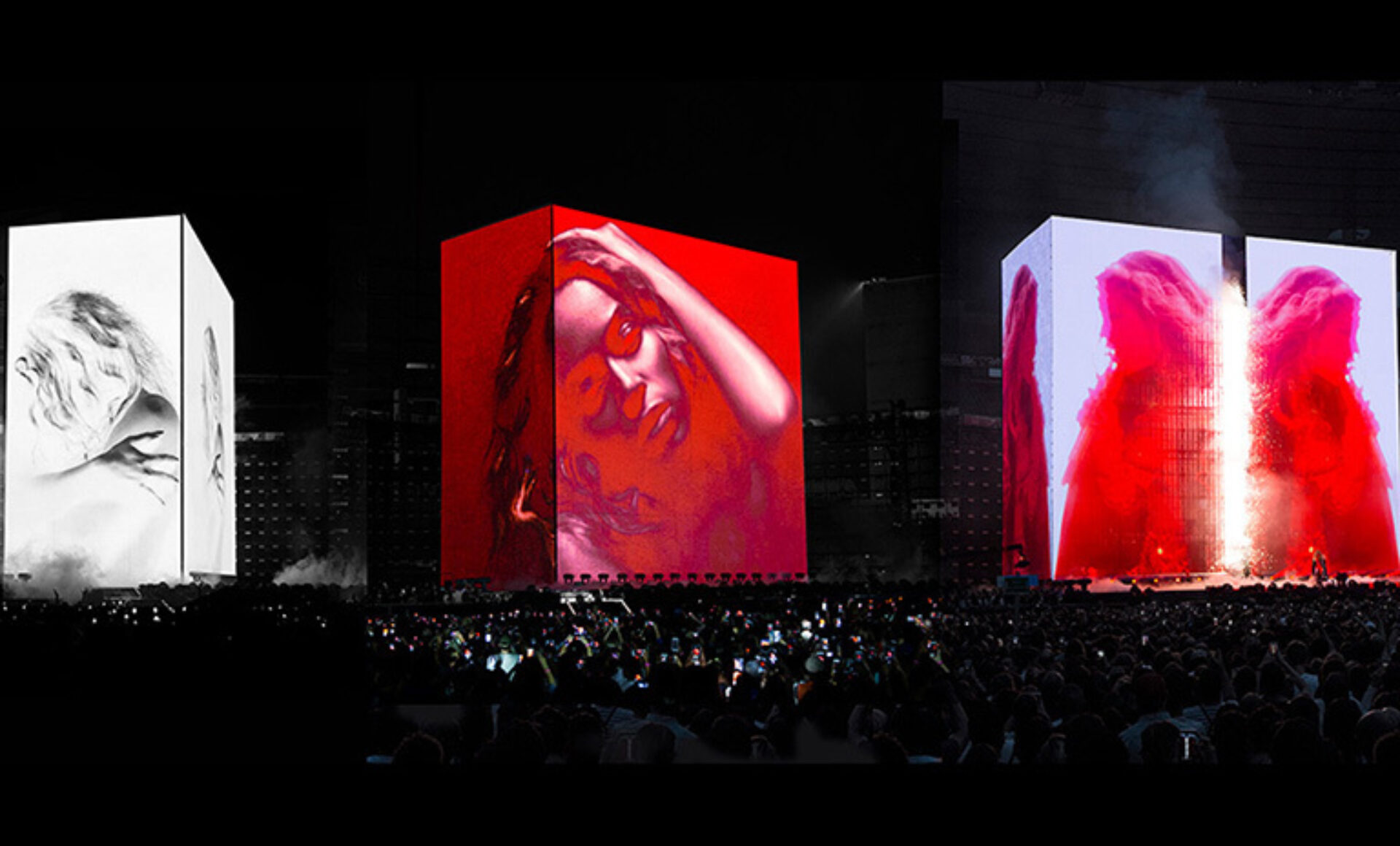

(Below: Indigenous Peoples Space by Tawaw Architecture Collective in collaboration with Smoke Architecture Inc., David T Fortin Architect Inc., and Elder Winnie Pitawanakwat)

Developing the Next Generation

It’s wonderful to hold the title of the first First Nations women architect in Canada, but the label isn’t as important to me as really creating a framework and doing the work that really transforms the field and creates an opening for the next generation to really take what I've started, and push the industry even further.

I probably have 10-15 years left to push in my career. And so my work at ASU is all about transferring this mode of working, and this sort of practice to the next generation. Growing up, I only saw myself represented in role models like teachers and social workers—those were the roles that people were pushing young women into and I thought, “Well, I don't really think I would be a great grade school teacher or social worker.” I was really strong in math and science, and very interested in the engineering of things so architecture felt like a natural fit.

Deconstructing Hierarchy

Part of what we're trying to institute at our firm is change—I’ve always felt a tenacity to push in the field of design. Thinking of the hierarchy that has been ingrained in architecture firms, I spent 15 years in the back room doing red lines and drawings, and I thought, “Gosh! I have so much to offer!” I wanted to change this, and at our firm, we started a fast-track leadership program. I don't want our staff to be sitting in the back room, not being able to contribute, because we want a broader range of ideas and to remove the barriers to leadership for these young amazing minds that are coming up in the field.

We also have a very casual office. I don’t care how you dress, we have dogs in our office, and wear shorts. I want staff to come to meetings with me and see how I talk to people. We develop through direct experience, come and engage with our communities, come and be a leader and develop your voice. I think it's through that sort of fast-track mentorship program that will develop the next generation of leaders in a much faster way and actually change the field while we change the processes.

Arturo Escobar, the author I previously mentioned, practices design in South America—his work is really transformative. So I encourage everyone to do a little research into his work because I think it's creating an opening, especially in South America where there is a really strong movement underway to get above the dominant ontologies. His work is one of the strongest leading the pack in this field.

We are one small part of, I think, a very large movement that is happening in the field. The amount of scholars, practitioners, and policy makers who are also interested in changing those dominant models are to me most inspiring. We are not alone, you know? 30 or even 20 years ago I felt like we were alone, now we are not alone. We are part of a large collective of people pushing to reimagine the field of design.

Visit the table of contents for more Perspective: Sustainable Futures