For Toni L. Griffin, it all began in a high school drafting class on Chicago’s South Side. As a student at Lindblom Math and Science Academy — then Lindblom Technical High School — Griffin, now a Professor in Practice of Urban Planning at Harvard Graduate School for Design and founder of transdisciplinary firm Urban American City, took a drafting workshop. There, she began to connect her proclivity for art to the process of design.

“I took two semesters of drafting,” said Griffin. “I had always drawn as a child, had never taken an art class, but my drafting teacher saw I had a pretty good aptitude for it. He would enter my drawings into these citywide competitions, and I won a few. One of my counselors at the time suggested that I go to a summer program at the University of Notre Dame for students interested in architecture.” She went, and while there, came to appreciate how architecture and design transform space. Intrigued, she later enrolled at Notre Dame and earned her bachelor’s in architecture. Her first job out of college was at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in Chicago, where the seeds for the next phase of her career were planted.

“My interest as a young architect, particularly in my 20s and early 30s, was I wanted to be a good designer. I wanted to be a great designer. I wanted to be involved in projects that made it onto the cover of Architectural Record,” Griffin said in an interview with CGTN America.

Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, Harvard Graduate School of Design | Founder, urban AC

Image courtesy of Toni L. Griffin

She was proud of her work at the prestigious SOM, where she worked on projects overseas in cities like London and Barcelona. During her seventh year with the firm, she started working in urban design. A project in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood proved to be a watershed moment.

“When I switched to urban design and planning, I was finally working in Chicago, and one of the neighborhoods we started working in was this neighborhood called Bronzeville,” Griffin said in the CGTN America interview. Bronzeville is about 10 minutes south of downtown and “part of the dividing line” between majority-Black and majority-white communities in Chicago, which is highly segregated. By working on the project, which was pro bono for a nonprofit, Griffin said she was exposed to the history of the city. “The history of the ‘Black Belt,’” — an area of the city Black Americans were confined to during the 1940s, due to discrimination and restrictive covenants — “the history of the Great Migration, where Blacks were migrating from the rural South to industrial jobs in the North but were actually segregated in certain parts of the city, even though Illinois was not a Jim Crow state.

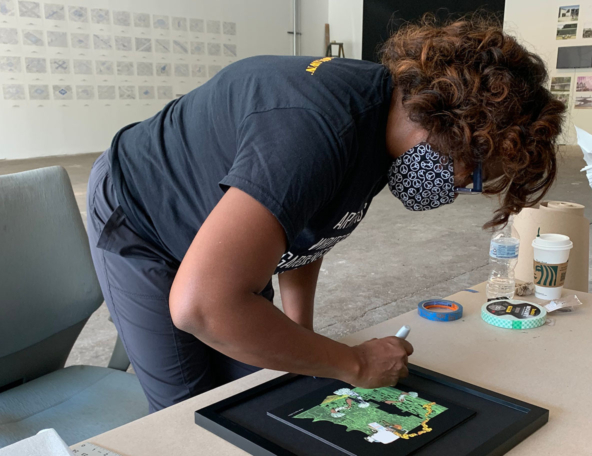

Photo credit: Sandra Steinbrecher

Image courtesy of Toni L. Griffin

“So, all of a sudden, all these other histories are unearthing about the place I grew up in. You begin to understand redlining and racial covenant practices, these policies that intentionally kept Black and brown people out of the path of progress and prosperity. It wasn’t until then that I started to connect my identity and my identity as an architect to the role that I could have in shaping cities and architectures,” she added.

In a way, a switch flipped — Griffin was able to blend her desire for design excellence with her deepening understanding of spatial injustice, and her impulse to make cities more equitable.

Transitioning from architecture to urban design and planning connected her to a broader constituency. It wasn’t just the developer and the architect, she was working with community-based organizations, the city government, residents, and businesses. “The ability to do what I love but also understand how my city is created, who makes decisions about what my city looks like, and what gets developed just awakened me to the disciplines of urban design and planning, and so that’s where I've been ever since,” Griffin said.

In Pursuit of Urban Justice

Through her work, Griffin seeks to increase urban justice, which she defines as “the factors that contribute to our economic, human health, civic and cultural well-being, as well as the factors that contribute to the environmental and aesthetic health of the built environment.” To understand how to implement it across cities and in public spaces, she asks herself a critical question: Am I challenging the agency of design?

After leaving SOM, she began working in the public sector to improve public space in cities across the country, from Chicago to New York and Washington D.C. In Newark, New Jersey, she served as Director of Planning and Community Development for then-Mayor Cory Booker's Administration. She spent about a decade in the public sector in an effort to understand its role in shaping cities. “It was never my desire to be a lifelong bureaucrat, but to really see how design could have agency in a different space of leadership,” she explained.

At one point, Griffin took some time off to explore other possibilities — she even went to culinary school. But urban planning was her calling, and it kept calling her back. Little did she know her next venture was just around the corner. The Kresge Foundation in Detroit was looking for someone to come and lead a citywide urban planning program to make use of all of the vacancies across the city.

Image courtesy of Toni L. Griffin

Image courtesy of Toni L. Griffin

In 2010, after many calls from colleagues and with the foundation, Griffin decided she was a perfect fit for the job and helped create Detroit Future City, a blueprint for the city’s future which involved deep local expertise plus thinkers from around the world. Soon after, she launched her own firm, Urban American City (urbanAC). A planning and design management practice, urbanAC works with public, private sector, and nonprofits to reimagine and rebuild just cities and communities.

In recent years, urbanAC has also worked in collaboration with the city of Detroit on a project called I-375 Reconnecting Communities, a proposal to remove a portion of Detroit's I-375 highway and replace it with an urban boulevard. The original highway construction occurred during the height of urban renewal, and dealt a devastating blow to Black neighborhoods. Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, two historically Black communities, were removed during the highway’s construction; the Reconnecting Communities project was designed to repair the harm, and urbanAC helped create a “reparative, restorative, and reconnective framework,” Griffin noted, to honor the history of what was lost.

Teaching Designers to Take Action

At Harvard, where Griffin is a professor, she recently taught a course called “Design for the Just City,” where students interrogated and explored case studies that showed ways design can impact urban justice. She also created a course called “Gentrification Debates”, where students unpack what gentrification is and how it correlates to positive or negative changes in neighborhoods. In the class, students examine the moment when a neighborhood becomes gentrified: “At what moment do you believe it’s hit a good spot of investment that’s benefiting everybody, versus tipping to a point where you feel like something harmful is going to happen, like displacement?” Griffin asks. “One of the things that embodies what I teach is the understanding of the trajectory of how neighborhoods change, and for what purpose, and who are gentrifiers?” she added.

Through Griffin’s Just City Lab, she and her team of researchers have created tools and courses that explore urban justice and allow designers to interrogate conditions that create injustice within cities and neighborhoods. While her firm UrbanAC typically examines and addresses issues of justice through practice, Just City Lab leans on theory and research to help deepen students’ and practitioners’ understanding of the possibilities of design and how it can address both spatial and social inequities.

Griffin understands designers play a critical role in addressing these inequities. But to do so, they must truly understand the root causes of injustice as part of the design process. “As designers, we’re all taught different ways of doing site analysis,” Griffin said, “but my practice and the Just City Lab goes a bit further and actually calls out an analytical process which is looking for the injustice embedded in the existing condition. The only way we can create a more just environment is to really name the injustice that’s there.”

Griffin understands designers play a critical role in addressing these inequities. But to do so, they must truly understand the root causes of injustice as part of the design process. “As designers, we’re all taught different ways of doing site analysis,” Griffin said, “but my practice and the Just City Lab goes a bit further and actually calls out an analytical process which is looking for the injustice embedded in the existing condition. The only way we can create a more just environment is to really name the injustice that’s there.”

Design can and does have the power to address social issues at a large scale. The key? Staying “vigilant and active,” Griffin said, in order to make sure “we have spaces and places that protect our rights” and enable a good quality of life and well-being. Griffin says the three important actions designers need in order to accomplish this are collaboration, transdisciplinary design, and trans-sectoral tables — spaces where everyone’s voices are included, from government officials to philanthropic and nonprofit community organizations to average citizens.

Photo credit: Naima Green

To her, change happens through disruption; it requires designers to activate their imaginations to design new structures and systems that promote urban justice.

“Designers are inherently futurists, right? And we have this unique capacity to envision something no one has seen yet. We have a very important role as part of our communities and cities and neighborhoods to help convene and bring imagination to the future just city we want to see.”

Toni L. Griffin